unitedhealth

UnitedHealth’s ‘great opportunity’ for its employees

Screenshot obtained by Tara Bannow/STAT

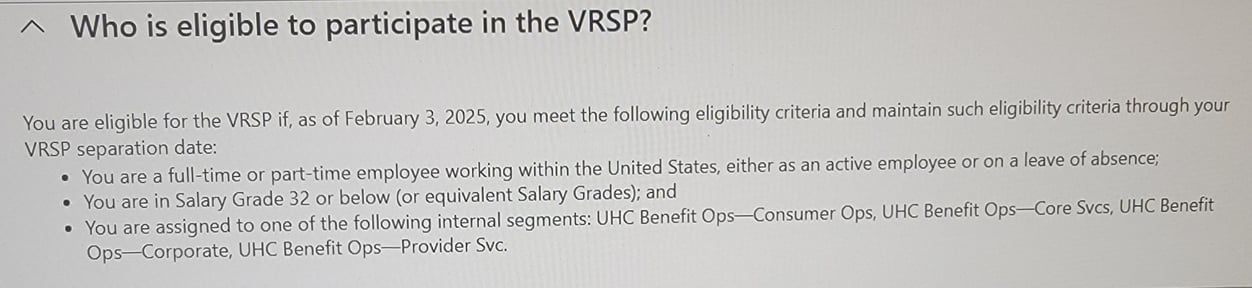

The corporate-speak was thick during UnitedHealth Group’s employee webinar last week, when it announced buyout offers for thousands of employees who work in the UnitedHealthcare insurance division. In a recording of the Feb. 17 meeting shared with my colleague Tara Bannow, a UnitedHealth executive told workers the buyouts were a “great opportunity” that would minimize the emotional and financial toll of job changes and “preserve the culture we’ve worked so hard to build.”

But then, Tara writes, something else appeared on the other side of cheerful buzzwords: a threat. “We’re optimistic that this voluntary separation offer will suffice to meet our workforce plans,” the executive said. “However, if it does not, additional employment actions, including potential involuntary reductions, may be necessary.”

UnitedHealth sent the buyout offers to about 30,000 people, according to Health Payer Specialist. The company won’t say how many workers it will axe if not enough people take the deal. The offers went to full- and part-time employees who help customers, manage claims, communicate with doctors, and others. UnitedHealth set a March 3 deadline to accept the buyouts, and most of those who do will be out May 1.

The company didn’t answer STAT’s questions about the buyouts.

Employees who reached out to Tara and posted on social media were frustrated, confused, and weary. Some had survived previous rounds of layoffs at UnitedHealth, and weren’t sure whether to take the offer or risk getting laid off later. And they didn’t feel UnitedHealth was being transparent enough in its communication. As one employee put it: “You don’t trust those people with the big fancy desks. They’re not being honest. They’re transferring our jobs to the Philippines.”

Others actually saw this as par for the course. One former employee told me: “In my experience, United has quiet layoffs and hiring freezes every four to six months before the annual shareholder meeting. They do this to demonstrate ‘cost controls’ on operating expenses, to meet share price expectations, and to maximize executive bonuses.”

government

Trump’s CMS is coming together

Mehmet Oz may be one of the wealthiest people to ever helm the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (if Congress confirms him). Tara got ahold of his ethics disclosures, which show Dr. Oz is worth at least $95 million and has big stock holdings in UnitedHealth and other health care companies that he would be regulating (he said he’ll sell those investments if he’s confirmed). He also married into a tree-trimming fortune.

A lot of health care policy at CMS is carried out by the administrator’s political appointees, and many of those positions are already set. Kim Brandt, who most recently lobbied for giant pharmaceutical companies, and John Brooks, who did health care consulting, are two new top CMS officials who would work under Dr. Oz and are already consulting with Elon Musk’s U.S. DOGE Service, according to POLITICO. Both were in CMS during the first Trump administration.

Drew Snyder, Mississippi’s longtime Medicaid director, heads CMS’ Center for Medicaid, and Peter Nelson, who was at a conservative think tank and who we mentioned last week, is atop the Center for Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight, which regulates Affordable Care Act marketplaces and ensures compliance with the surprise billing law.

We still don’t know who’s going to lead the Center for Medicare. Ing-Jye Cheng, who has been at CMS since 2009, is the acting director. But it’s worth watching two new political appointees: Alec Aramanda, a former congressional staffer and lobbyist who was in Trump’s CMS the first time, is the Center for Medicare’s principal deputy director, and Joe Albanese, most recently of the conservative Paragon Institute, is a policy adviser. Albanese and others at Paragon have written extensively about their support for major Medicare Advantage payment reforms that insurers oppose.

glp-1s

The real slim shady

GLP-1 weight loss drugs like Wegovy and Zepbound have big price tags, but they are so effective at helping people shed pounds that many employers are grappling with whether they should cover them. But…what if these drugs are becoming too effective?

My colleague Elaine Chen spoke with people who are enrolled in a clinical trial for Eli Lilly’s next-generation obesity drug, including one person who has lost almost a third of his body weight and is forcing himself to eat peanut butter so he doesn’t wilt away. As Elaine writes, these concerns “are an outgrowth of drug companies’ race to the bottom — an intense competition to develop drugs that can deliver greater and greater topline weight loss.”

Read Elaine’s story, which explains how the next versions of these drugs may be too powerful and how an intense focus on weight loss may not be in patients’ best interest. This also could make for some very interesting insurance coverage decisions.